Let's learn Hexagonal Architecture!

Since humans have been able to build structures, we have formed techniques and principles that other builders can apply, so they aren’t condemned to relive the same mistakes. Even the most audacious architectural marvels, such as the spectacular Duomo in Florence, aren’t just the isolated achievements of a maverick polymath; but the considered applications of principles and techniques learned from previous generations to solve a very unique problem.

Software Development is similar (probably only in this regard) in that we share design patterns, principles and architectures distilled from the similarities between solutions to the same kind of problems. Learning of these and applying them in the appropriate situations prevents us from having to relive the difficulties faced by other members of the community.

One such architecture that I wanted to write about is Hexagonal Architecture (more formally known as Port & Adaptors), created by Alistair Cockburn. It’s a very simple architecture that I’ve been applying recently to help separate my application’s core functionality from technical infrastructure; a separation that is useful when I know the infrastructure will change. So, I thought I’d try and further cement my understanding by explaining it…

Let’s start with a problem

Every architectural pattern is trying to provide a solution to a common problem, so let’s look at a suitable problem…

At the energy company I work for we have a lot of customers in our systems and with the natural ebb and flow of any large organisation, we are regularly opening and closing accounts. Let us imagine then, that we’ve been tasked with writing a system that will automatically close these accounts. We do this by:

- Removing all meters associated with the account

- Telling the system managing the account to close it

A simple enough task until you learn that there are numerous sources wanting to close accounts, some want to put CSVs into S3 buckets, others favour HTTP endpoints and Customer Services have always wanted a UI. Similarly, downstream systems for managing accounts are also numerous.

The quick solution

We could just start hammering out code, tightly coupling ourselves to third-party systems and call it a day with a few high level tests — with no abstractions or boundaries to think about, we’d be done in a jiffy! The business would rejoice and we could move on to the next task… well, that is until our system inevitably grows in complexity to a point where our lack of concern for architecture is going to negatively affect us:

- With no clear boundaries between the responsibilities, any developer reading the code will have to hold a lot more about how it operates in their head. The same chunk of code might touch a database, an account management system and be sprinkled with terms specific to a domain

- Modularity wasn’t a concern at the time as we knew the technologies the business wanted, but the request to add a new external system only adds to the complexity

- We’ve tightly coupled our technologies to the application’s core functionality, so testing requires complicated mocks or real implementations running locally — the former affecting how easy it is to write tests and the latter slowing down the feedback cycle more than necessary

The considered solution

A little research into this type of problem shows that it isn’t unusual. In fact, we can even watch the author of Hexagonal Architecture, Alistair Cockburn, describe problems like ours and the architecture he refined, to make a maintainable solution..

Let us apply the main tenants of this architecture to see how it influences our approach to a problem like this, then afterwards we’ll learn more about the particulars of this architecture.

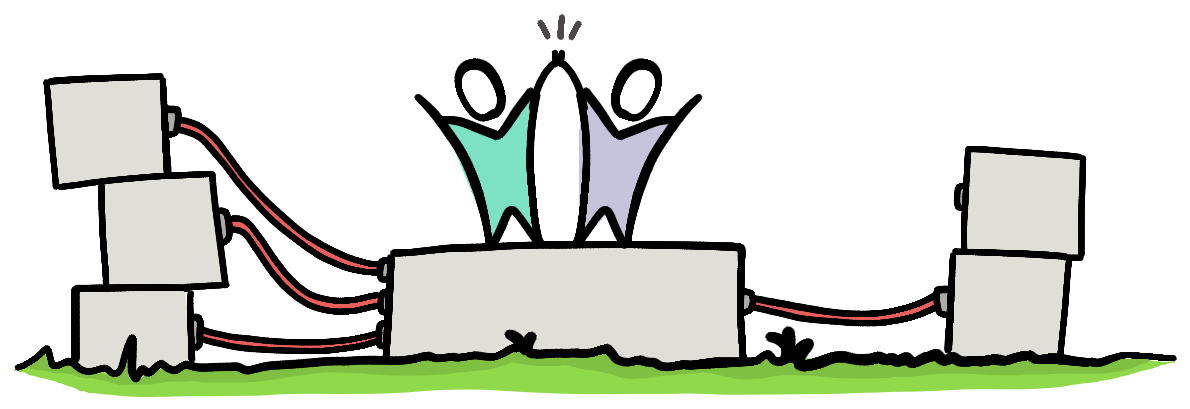

Modular inputs/outputs

We can see from the original problem that modularity is key! We have numerous inputs and outputs that will likely change over time, and we don’t want to pollute our core functionality of closing accounts with particular technologies, as this will only hamper our ability to change either of them in the future. Instead, we should look to modularise interactions so our core functionality no longer depends on any particular implementation.

Isolate business logic

Turning our attention to the core functionality, it will be generic across the various inputs, since it is just removing meters and then closing the account. We could isolate it from external interactions by creating contracts that must be implemented by any component wanting to interact with it, allowing us to:

- Scope the language of the business logic and its contracts to our domain – making it easier for developers and business users to understand

- Test the business logic in isolation from technical infrastructure

Having just read the result of applying Hexagonal Architecture, let’s delve into a little of its theory…

What is Hexagonal Architecture

The only way for humans to deal with complexity is to avoid it, by working at higher levels of abstraction. We can get more done if we program by combining components of useful functionality rather than manipulating variables and control flow; that’s why most people order food from a menu in terms of dishes, rather than detail the recipes used to create them.

— Chapter 6. Object-Oriented Style - Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests Book

The purpose of Hexagonal Architecture is pretty straight forward, it focuses on separating your application’s core functionality from the interactions it has with the outside world. This simple act of separating responsibilities has numerous benefits:

- Interactions with technical infrastructure (calls to DBs or external APIs) being modularised:

- These interactions can be tested in isolation from the core functionality

- The technical infrastructure can be swapped with little impact on the rest of the application

- Core functionality is isolated from technical infrastructure:

- The code for the app’s core functionality isn’t punctuated with calls to databases or external APIs, making it easier to read and maintain, we can even use the language of the domain

- Core functionality of the application can be developed and tested independently of its eventual technical infrastructure

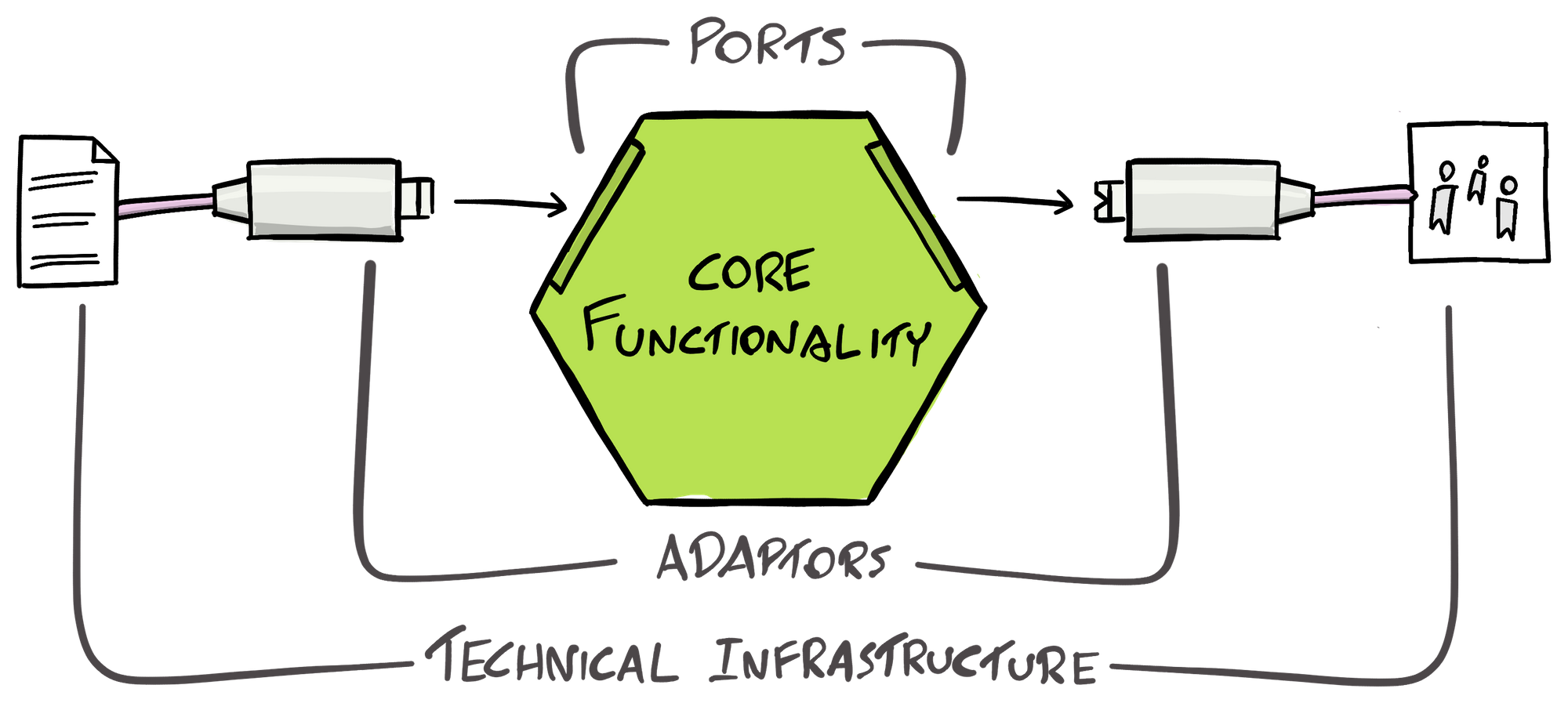

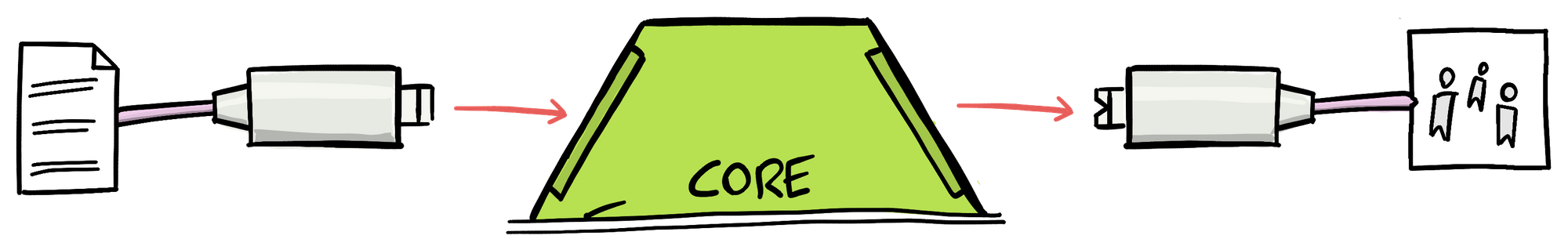

So how does this architecture suggest achieving this separation? Well, the secret is structuring our application’s code around two components; ’Ports’ and ‘Adaptors’.

Components of hexagonal architecture

Ports and Adaptors provide a way of thinking about the interaction between the core functionality and the technical infrastructure of the outside world:

- Ports - these form the APIs through which the core functionality and outside world interact. Each port has a specific purpose, i.e. one port could allow an adaptor to ‘close an account’, whilst another port might allow the core functionality to ‘manage an account’

- Adaptors - Each adaptor is designed to manage the communication between a technology and a particular port, i.e. you may have an adaptor that reads account IDs from a file and invokes the core functionality’s port for ‘closing an account’ with each of these IDs

Let’s take a closer look at each of these components… rest assured though, neither are anymore complicated than applying SOLID principles.

Ports

These are the contracts for interacting with (or by) the core functionality. Each one is designed with a specific intent, such as ‘for notifying X’, ‘for creating Y’ or ‘for closing account Z’. By using them to create a boundary around our core functionality, we can prevent it being coupled to technologies and allow us to consistently apply the language of the domain this process belongs to.

If we imagine the core functionality being in a class, then a port is just an interface, either exposing a method on the class, that is invoked by an adaptor or forming a dependency in its constructor. The approach depends on whether the core functionality is being interacted by the outside world (ports on the left in the picture above), or is trying to interact with the outside world (ports on the right in the picture above).

This is what ports look like in the code:

// Class containing core functionality

class AccountCloser implements CloseAccount {

// This is a port ‘for managing customer accounts’

private accountManager: AccountManager;

public constructor(accountManager: AccountManager){

this.accountManager = accountManager;

}

// This is the port ‘for providing the ID of the account to close’

public async closeAccount(accountId: string): void {

// Logic to remove meters and close account...

}

}

All we’ve really done is just followed the I and D in SOLID:

- Interface Segregation - having interfaces specific to a single intention (port) so adaptors only have to know about the methods that are of interest to them

- Dependency Inversion - decoupling the AccountManager from an actual implementation, allowing us to pass any implementation (adaptor) in

Take note of how easily we can now test our core functionality.

Adaptors

Adaptors encapsulate the interaction between a technology and a port. This often involves some form of transformation between a technology specific model to that of the port, i.e. an adaptor could be a component that receives a specific HTTP request, extracts and validates a parameter from it and then passes this parameter to a port as an Account ID.

Depending on whether the adaptor is calling a port (left arrow) or the core functionality is calling an adaptor (right arrow), you’ll write your adaptors differently. Let’s have a look at how to write each type of adaptor.

Writing an adaptor that calls a port

In order for the adaptor to call the core functionality it must know about the port, so in the example below we inject in the port, in this case CloseAccount.

// Example adaptor ‘for providing the ID of the account to close’

class ApiGatewayAdapter {

private accountCloser: CloseAccount;

// Injecting the port ‘for providing the ID of the account to close’

public constructor(accountCloser: CloseAccount){

this.accountCloser = accountCloser;

}

public receiveApiGatewayEvent(event: APIGatewayProxyEvent) {

const accountId = this.extractAccountId(event);

// Calling the port

this.accountCloser.closeAccount(accountId);

}

//...

}

Writing an adaptor that is called by core functionality

To create an adaptor that will be called by the core functionality, the adaptor needs to implement the port. Below we want to create an adaptor that allows the core functionality to manage an account, so it implements the port/interface AccountManager.

This type of adaptor is provided to the core functionality in the setup of the application (composition root).

// Example adaptor ‘for managing customer accounts’

export class AmazingEnergy implements AccountManager {

private amazingEnergyClient: HttpClient;

public constructor(amazingEnergyClient: HttpClient){

this.amazingEnergyClient = amazingEnergyClient;

}

public async closeAccount(accountId: string): Promise<void> {

// Make request to close the account…

}

public async getActiveMeters(accountId: string): Promise<Array<Meter>> {

// Make request to get active meters…

}

public removeMeter(accountId: string, meter: Meter): Promise<void> {

// Make request to remove meter…

}

}

// Example of passing this adaptor to the AccountCloser

// new AccountCloser(amazingEnergy);

There we go, nothing too complicated. We can now write any number of adaptors that can interact with our account closer, without having to touch the core functionality.

Next time… applying Hexagonal Architecture to our problem

In the next article we’ll look to apply what we’ve learned to create a fully deployable solution (minus the industry backend of course).

Until then however I hope this article has provided you with enough knowledge to apply hexagonal architecture when you’re faced with a similar problem. Just remember to apply it wisely, as no pattern is a panacea to every problem.